Lessons From the Space Race: 3 Steps to Better Product Decisions [Mind the Product]

What makes a great product decision? The answer to this question is like the Holy Grail of product management: it promises success and prosperity but no clear evidence that it exists. In this post I examine the way I think about the path: what has worked for me and helped me grow as a product manager and decision maker.

Let’s go back 50 years. The US is actively involved in the Space Race with the Soviet Union, and NASA starts an ambitious project: developing a spacecraft to land on the Moon. The problem was that no one knows what the Moon’s surface is like. Is it soft and powdery? Is it covered with needle-sharp crystals? Or is it formed of large glacial boulders?

It all affects what the weight of the machine should be, the materials it should be built with, and how it should move. You might think that it’s impossible to design a vehicle given such ambiguous conditions, but doesn’t it look similar to what we do while developing a new product or feature? Let’s walk through the process.

What’s your first step when you approach such a problem?

Collect Data

Let’s define what data is. It doesn’t always mean “numbers”. It is simply information that can be presented in a numeric form, but qualitative insights are also considered to be data. It doesn’t matter if you write SQL queries or talk to your customers, both are “collecting and analysing data”. In Facebook we’ve seen that the most interesting discoveries happen when a data scientist and UX researcher work together and look at the same problem from different angles.

Data also isn’t equal to “users”. If your product doesn’t yet exist, you still have a variety of data sources you could use. There are marketing intelligence tools like SensorTower, research techniques like competitive analysis or job story research, MVPs in a form of, for example, simple websites or ads that would test your value proposition without building anything. But do you know what is the cheapest and the best tool that only very few people use? Google Search. For some reason, people prefer to go to a coffee shop and talk to some random strangers before, or even instead of, digging into what’s already been created.

Let’s go back to the Moon project. What kind of data could we collect? No one has been to the Moon before but the cost of failure is tremendous so at least some data is better than none. We could use pictures of the Moon to take measurements, assess the structure, and make assumptions about the Moon’s geological formation. That’s how scientists working on the project came to the final hypotheses about how the Moon was formed.

It’s important to remember, though, that collecting the data isn’t about “just collecting the data”, it’s about understanding the impact of it. Your goal is not to always make the right decision but to invest the right amount of time into making this decision according to its importance.

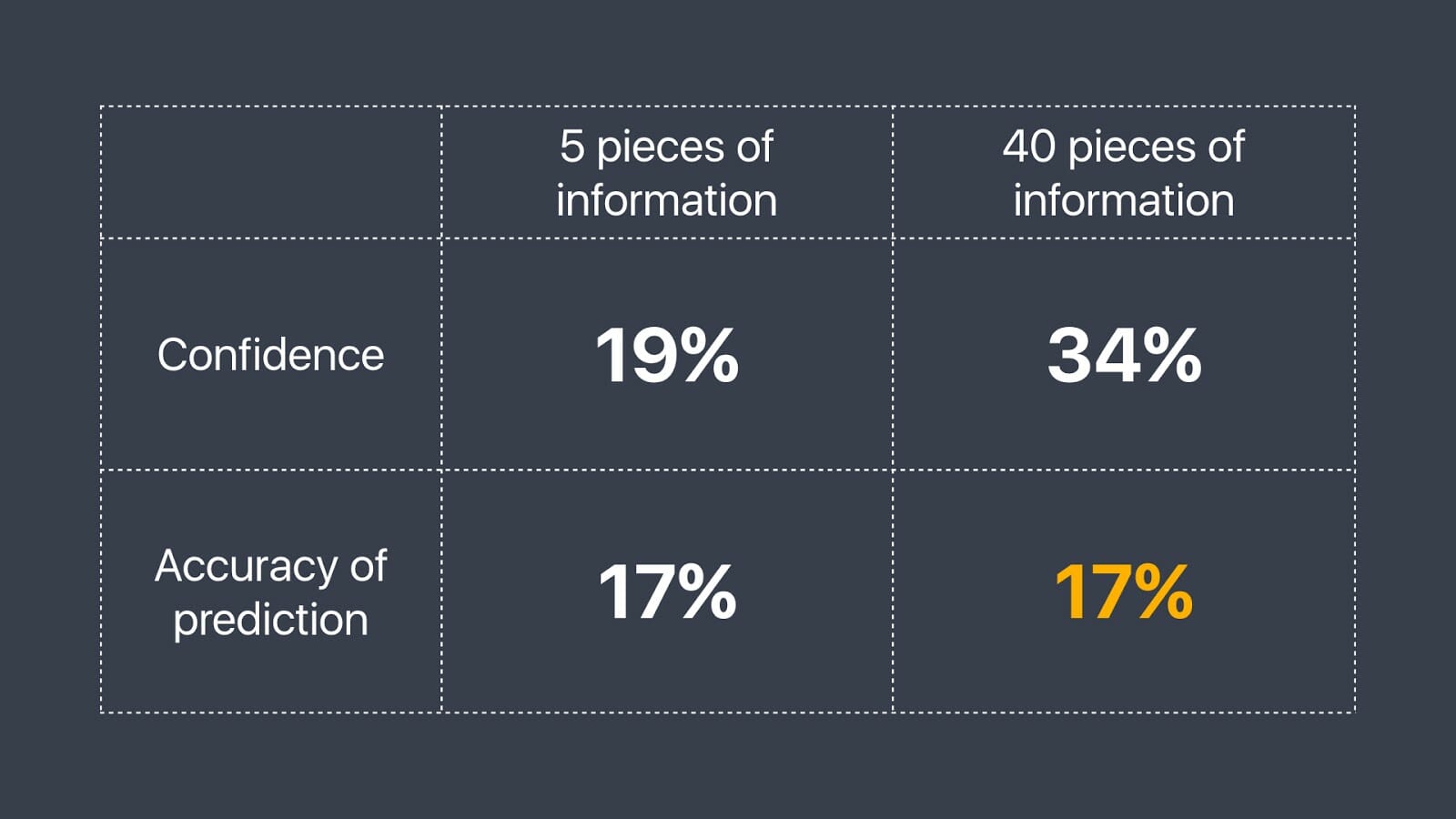

In a fascinating study done by Paul Slovic, a group of professional horse-race handicappers was asked to make predictions about a race. At first, they were allowed to pick only five pieces of information: with that, they were able to correctly predict the outcome nearly 17% of the time. They were also 19% confident in their predictions.

Each handicapper was allowed to select more and more data, and their confidence in predictions nearly doubled going up to 34%! But guess what? Their actual results stayed roughly the same. Additional data didn’t make their predictions better, but it made people believe that they were making better decisions.

Why is this a really bad situation? First, obviously, you spend your time and resources to collect unnecessary and redundant data. Second, there is so much data that you lose sight of what really matters, eventually falling into a classic “analysis paralysis” trap and end up fearing to make any decision at all.

To understand how much time you should invest in the decision-making process, you should try to define impact by the sum of positive and negative outcomes: what do we expect to happen when this decision is made?

- Do we expect to unlock new markets or significantly improve user experience?

- Can it lead to wasting months of work on development?

- What is the possibility of this new product or feature damaging our brand or leading to customers’ churn?

- Will we be able to reverse this decision?

It’s like the chicken or the egg dilemma – you never know for sure what the impact would be until you invest some resources into understanding it better.

That’s where the second step comes in.

Apply Intuition

Intuition is all your previous experiences combined and recognised in a new situation by some cues. According to Daniel Kahneman, a Nobel Prize-winning behavioral economist, “intuition is thinking that you know without knowing why you do”. This is precisely the mechanism we need to assess the impact even before we start digging into data.

Let’s consider two examples: building a new product and changing the colour of the button in the existing product. Which one would have a higher impact on our business? A new product can unlock a new market for us while a colour change is just a local optimisation. It doesn’t mean though that we shouldn’t do the former one, it just means that we should invest fewer resources into making a decision about that change. It’s a classic pitfall for junior product managers: they would spend almost equal amounts of resources on decisions of different importance.

So the question really is how to develop an expert intuition? According to Kahneman, there are three conditions that need to be met.

First, there has to be some regularity in the world that you can pick up and learn. Take, for example, an e-commerce website: it’s a pretty well-defined space, and unless you are trying to reshape the whole shopping experience, there is no need to reinvent the wheel. You can safely rely on the best industry practices to build a showcase, a shopping cart or a sign-up experience.

The second condition is “a lot of practice”. And the third condition is immediate feedback.

Despite all the experience in the world, there are some areas where you just can’t develop an intuition. Complex research questions such as “how do you help people quickly find information on the internet” or “how do you help people get from point A to point B in a fast, cheap and convenient way” have a pretty unique set of constraints and unknowns and are unlikely to be repeated in the same way. In such cases there are no best practices you could learn from, and even if you’ve worked on such problems for years, you shouldn’t rely on your intuition too much. (To learn more about the different types of problem spaces, check the Cynefin framework developed by IBM researchers.)

Here’s another pitfall. I often see that people working on new complex products use their gut sense, not only to make an assumption about the impact of solving the problem, but also to come up with a solution itself. If we trust Kahneman, this is exactly when we shouldn’t listen to our intuition. Moreover, it’s the highest point of uncertainty that you possibly could have, and the impact of your decisions at this point can be game-changing for your business.

It doesn’t mean though that intuition then becomes useless, just that it should be used differently. Consider it as a list of possibilities rather than direct guidance: as soon as it “dings” in your head, recognise if it is an assumption or a fact, and if it is an assumption, find a way to test it. Then even if you can’t rely on your intuition to address a complex problem, you will still have a bunch of accompanying smaller problems where your experience and intuition can be applicable. In our “getting people from A to B” problem, while you can’t choose which hypothesis to trust solely based on your intuition, you can still use it to understand when you’ve collected enough data or if your dataset looks right. Intuition doesn’t give you a solution but it helps you to ask better questions and consider more possibilities and risks.

The NASA Moon project was directed by Phyllis Buwalda, and it was a new and complex problem. So she:

- Assessed the situation and the impact;

- Collected data to form three solid hypotheses;

- Understood the trade-offs between collecting more data (but probably not going any further with it) and the cost of engineers and designers not being able to work without a specification;

- Understood that the only way to know for sure which hypothesis is true is to build a machine and send it to the Moon.

And there is still one component missing. Although intuition and data can create a very powerful foundation for your decision making, when the stakes are high, and the problem space is new, you need to add another layer.

Foster Creativity

Data and intuition orient you towards the past or the present, but if you want to reshape the future, you need to be creative.

There are many different definitions of creativity, I personally really like the following by American psychologist Dr. E. Paul Torrance: “creativity is a process of becoming sensitive to problems, deficiencies, gaps in knowledge, missing elements, disharmonies, and so on”. Following this definition, I believe that creativity has a few important components:

- Humility. Being humble is the first step to being creative. It makes us vulnerable but it also makes us receptive to new information. It makes us wonder and ask questions.

- Diversity. Steve Jobs once said that creativity is “just connecting things”; many discoveries or business strategies come from linking two previously independent areas. It means that sometimes, instead of going deep, you actually should go broad.

- Courage. You shouldn’t be afraid to look dumb when you are questioning conventional wisdom and challenging foundational concepts. And you should always be ready to fail.

In our decision-making process, creativity means that you go one step back and challenge all the key assumptions you made.

Adam Brandenburger, Professor and Director of the Shanghai program on Creativity+Innovation, suggests four questions to start thinking creatively:

- Contrast: What pieces of conventional wisdom are ripe for contradiction?

- Combination: How can you connect products or services that have traditionally been separate?

- Constraint: How can you turn limitations or liabilities into opportunities?

- Context/Analogy: How can far-flung industries, ideas, or disciplines shed light on your most pressing problems?

So what did Phyllis Buwalda, director of the NASA program, do? She tried to gain a new perspective through drawing an analogy to make the final choice. Here is her description of the lunar surface: “Hard and grainy, with slopes of no more than about 15 degrees, scattered small stones, and boulders no larger than about two feet across spaced here and there.” How could she possibly know all those little details? Simple: if you look closer, what she describes is very similar to the surface of the Southwestern desert on Earth! Phyllis combined her previous research with an analogy: her hypothesis was no worse than the others being considered, and it was something that engineers knew how to tackle so it helped speed the project along.

The name of the NASA program was Surveyor; the first machine successfully landed on the Moon, took detailed examinations of the lunar surface and became a game-changer in preparation for the Apollo program.

Decision-making process is a very complex operation, and what makes it even more difficult is that usually you don’t know what would have changed if you’d decided otherwise. Nevertheless, when I use these three components – data, intuition, and creativity – I feel that my decisions are more weighted and multi-faceted. Take data alone, and you might end up with a very limited view. Rely only on intuition, and your decision might be quite biased or overconfident. Use only creativity, and you’ll end up with a disconnect between your fantasies and reality. Even used all together they won’t give you 100% certainty. But what they give you is a rich and holistic picture that empowers you to go to the Moon and back.

The post Lessons From the Space Race: 3 Steps to Better Product Decisions appeared first on Mind the Product.

Source: Mind the Product https://www.mindtheproduct.com/2019/07/lessons-from-the-space-race-3-steps-to-better-product-decisions/

Post a Comment